On Being Painted

I.

In the middle of August I sat for a portrait. Over the course of one week I sat still for a total of twelve and a half hours, staring at a single fixed point. The studio was draped in an intricate system of ropes and pulleys connected to black curtains, a system designed in order to manipulate the light entering the space. The fixed point I stared at was a knot tied in the middle of a hanging rope, a knot which appeared to me as a multitude of different things during those twelve and a half hours. I have listed a selection of things the knot appeared to me as below:

The head of a lurcher

A bride

A shrunken voodoo head

A wizard’s hat

Two children, entwined, like vintage kissing figures

A cutlass

The knot in the middle of the rope appeared as many other things which I can’t recall, but what I do recall was my fascination with its changing form. Nothing moved, nothing changed, yet as the time passed it seemed the knot in the rope was completely alien to the thing it had been thirty minutes prior.

I have never been painted before. What excited me about the notion of being painted was to see myself made concrete through someone else’s eyes. I wanted to know what I looked like. Did I have the faraway look of a dreamer, did I have determined eyes, or perhaps, as I was once told by a portrait photographer, an imperious face? What form would I take in oil?

There were three empty chairs in the studio, placed on small, raised plinths. I sat in the middle. Each chair was flanked by two blank canvasses. One model, two painters. One painter began talking to me at the beginning of our first session, me sat on the raised chair, her looking up at me inquisitively. She asked me what I did, then when I responded I was freshly graduated, asked me what I had read at Cambridge; English, I said, and began chatting about Elena Ferrante. As the painter spoke to me, she looked at me searchingly, moving her head in a way people usually do not during normal conversation, her neck swerving left, then right. She looked at my face but I had the overwhelming feeling that she was seeing something else, looking through to my bones. I felt she was seeing my skull, my eye sockets, my jawbone. Anatomical. As we talked she continued looking at me in this way, nodding and murmuring in assent, making light marks on the canvas as she did so, eyes flicking imperceptibly between me and the canvas.

When I took up my pose, angled slightly to the left and staring upwards, I could see her in the peripheral of my right eye. Observing, eyes flitting, making marks. It thrilled me to be looked at like that.

II.

Elena Ferrante’s novella The Days of Abandonment opens with the protagonist’s husband abruptly leaving her. It is a personal loss that distends her life, turns her desperate and furious, yet also leaves her feeling formless: ‘Where was I coming from’ she asks to no one in particular, ‘What was I becoming?’ When I say she feels formless I see this in Abandonment as a type of uncertainty, an inability to discern between things; being unable to say, with conviction, this is me, this is my life, and here are the things, material or otherwise, that total my life. In My Brilliant Friend — the first in Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet— the brilliant friend in question, Lila, experiences episodes of psychic distress that emerge as episodes of formlessness, episodes called ‘dissolving margins’. When the margins dissolve, Lila experiences a sensation where ‘the outlines of people and things suddenly dissolved, disappeared.’ A formless life is one without senses, without solidity; no touch, no sight, no smell. Lila’s dissolving margins also appear to be moments in which she fears a formless life that she cannot control, a life which time and time again is tried to be contained and given form in the Neapolitan Quartet through the act of writing. The continual tension of the novels (insofar as I have read them) seems to be the push and pull between writing and living, the question of how to contain a life within writing. Even the name for the episodes, ‘dissolving margins’, evokes the sense of a piece of lined paper whose edges bleed off: the inability of form to contain words, to contain a life.

I am reflecting on Ferrante’s character’s formlessness because since graduating from my postgraduate degree, the overwhelming sense in my life is one of dissolving margins. The outlines of people so familiar to me disappeared from my mind, they are scattered across the globe, and I suddenly have no sense of having ever been with them at all. How the things in my dearly beloved attic bedroom were arranged escapes me. Not only does my past feel to be lacking shape because I am no longer in it, my future and who, or what, I am becoming remains a large question mark, equally as formless as the past; Find a good job, travel the world, write a novel, do a PhD, buy a house, make my millions, generally rise above my allotted station in life. This is a future in which I do all the things five years in higher education is supposed to allow you to do. I also daydream about leaving everyone behind and moving to Mexico, where I imagine I will sell silver and spend my days sunbathing and reading with my friend Oli. Other times I imagine the future to be dull, working a 9-5 in a commuter town, a life which is the epitome of the working-class drudgery and debt I have spent many years trying to run from. In the present, I have been listening exclusively to CMAT’s new song EURO-COUNTRY as I sweep and mop the floors of the pizza restaurant in which I now work, crying while emptying the glass bin at 10am, to the inquisitive onlooking of elderly passersby. Suddenly it seems impossible I ever constructed an essay, that I ever will again, that I was able to turn my thoughts into form, structure, style. That’s postgraduate malaise, my boyfriend tells me over the phone as I cry, right down to a T.

I never paid much attention to form during my five years as an English student. In literary studies, form is the kind of text you’re looking at. Is it a poem, play, novel? Formal qualities bored me, I never wanted to know why I felt a certain way about a certain poem or book, I just accepted that I did. But now I’m reflecting on it, of course my academic work thought about form; what happens when a poem is condensed down into a digital meme, a novel turned into an accessory? But when I think back to the classrooms of my undergraduate degree, questions of form bored me.

Form, of course, is fundamental to everything. Our ways of describing, creating, talking, all of them require an understanding of form: this is how I see this, what do you think of how I see this? To make something solid, to give what one sees form through construction —be it writing, painting, or otherwise— is to make the way in which one sees the world tangible and therefore valid. It is partly a bit of self-presentation. At the end of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, Lily Briscoe finishes the painting which has taken her the length of a life to complete with a sudden intense movement, made up of a singular stroke: ‘Yes, she thought, laying down her brush with extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.’ Her vision, had, made, done, through the forms drawn on her canvas. What does it mean to have had a vision and to give it form? What happens afterwards and during this process?

III.

In case you have never been painted by traditional portrait artists before, I will describe to you their movements. The very first step is a shaping of their forefinger and thumb into a square, a shape which is then held up in space to delineate what their subject will be and where its margins are. While doing this, the painter squints frequently and moves the square made with their fingers closer and further away from their eye, until satisfied with the margins of their subjects. As my two painters did this, they asked each other what they thought of the subject and the composition; Difficult, one said, but I’m up for the challenge, replied the other.

After deciding upon the margins of their subject, the painters step rhythmically backwards and forwards, using a traditional method called sight-size. Walking five paces back, they would look at me, look at their canvas —tilting their head cat-like— then walk five paces forward, set down one stroke, then take five paces backwards again. One of the painters while walking towards me would use his paintbrush as a kind of conductor’s baton, making hand movements that moved over my face to the canvas, mimicking the lines and shapes he wanted to replicate there. Often, after placing the lines down, he would make an outburst of dissatisfaction; what I thought of this, as I sat very still, was that the in-between space was the most generative for this particular painter, that this was the place where he was most fully in cohesion with his artistic vision. It was in that pose, holding his arm like a conductor’s baton, between having made a mark and not having made a mark, where he seemed most at peace with what he was doing. Otherwise, he seemed to be completely unhappy. In the corner of my eye, the other painter with the searing gaze worked calmly. I did not hear her sigh once.

In the determination on myself as a subject — difficult — the painters expressed a kind of vexation. What they saw was challenging, but they appeared excited by this. Why this happy vexation? Brian Dillon, when discussing the list as literary form, asks ‘isn’t the very act of setting things down evidence of some vexation, a clue that something is missing?’ Something is missing from the world when we give something form, namely, a concrete version of how one sees it. It is an act of self-presentation, of giving a bit of yourself away and asking to be liked or scrutinised in return. Now I reflect on being painted, I think the act had very little to do with me, and more to do with the painters themselves.

IV.

The idea of modelling for artists has always intrigued me because I find it alluring and satisfying to see yourself through someone else’s eyes. I suppose then that my initial desire to be painted could be articulated as a desire to be put in order, to be given form during a time of formlessness. My desire to write also perhaps stems from this desire. I want to put in order the world as I see it, to make things orderly, despite what I believe to be their fundamental disorderliness.

I have often found it difficult to articulate my own desires or my own feelings, my own likes and dislikes. An ex-housemate of mine once wrote down a list of everything she liked, from food to colours to films, because she found she often forgot how to respond when asked about her favourite things. I tried to do the same thing and found I couldn’t; no answer to the question ‘what is your favourite food’ seemed to feel right, so I gave up. But I think that both of our approaches —the making of the list and the inability to make the list— speak to an understanding of the disorder of things, attempts to give form to formlessness. In creating a list, my housemate gave form to herself. I gave up, but I still ended up with something, a half finished list, a question unanswered.

The disorderliness of thoughts is why the act of writing is nearly always vexing for me. I find writing nearly always misses the mark of what I am trying to say. There is a gulf between the oblique form of things in my mind and the connections they fire off to their final form on paper. But there is little I enjoy more than the process of trying to bridge these two islands. Like the painter, I am most content when I am between imagination and the act, when I am sat trying to navigate the area between formlessness and form, thinking about how best to set it down. It is in this state where the knot in the middle of a piece of rope might become anything from a lurcher’s head to a pirate’s machete.

I have said that being painted had little to do with me and everything to do with the painters. This is true but not strictly so. There was a kind of push and pull between us. One day I was incredibly tired and I could feel my eyes drooping and my body twitching involuntarily. I had also, thoughtlessly, worn different earrings and put on makeup. Small changes, but rather large changes to a portrait artist. I could feel the discontent of one of my painters with both these changes and my bodily twitches, and apologised profusely for my poor sitting. Another day, I was asked to put my hair up so the two painters could better paint my facial features. The next day, I was asked to wear my hair down. You’re a completely different person with your hair down, sighed one painter, looking between me and the canvas. It is a twin endeavour, to give something form. It requires a relationship between form and formlessness, between articulation and disarticulation. The two require each other and perhaps hinder each other.

V.

At the end of our master’s degrees, my friend Katie kept recounting a passage from a book a friend of hers had read. The passage was something to do with how the book’s narrator hated transitions; she hated Sunday evenings, she hated the awkward bit before having sex with her husband, she hated getting into the pool. When getting in the pool, of course the narrator loved being in the pool. But just before, as she thought about how cold it would be as she acclimatised, the narrator was dreadfully unhappy. We’re getting in the pool! Katie would say with a mix of dread and glee, as we all shared fears and cried about our respective futures. Oona told me she wanted a new haircut, but that she was going to wait until she knew what she was doing next. It’s always good to go into a new phase of life with a new haircut, she told me, and I nodded in solemn agreement.

What my friend’s conversations towards the end of our time together had in common was the notion of formlessness, of dissolved margins: what would our futures look like, what would we be like, as we left the comforts of higher education for the vast unknown? So being painted came to me during this time of formlessness.

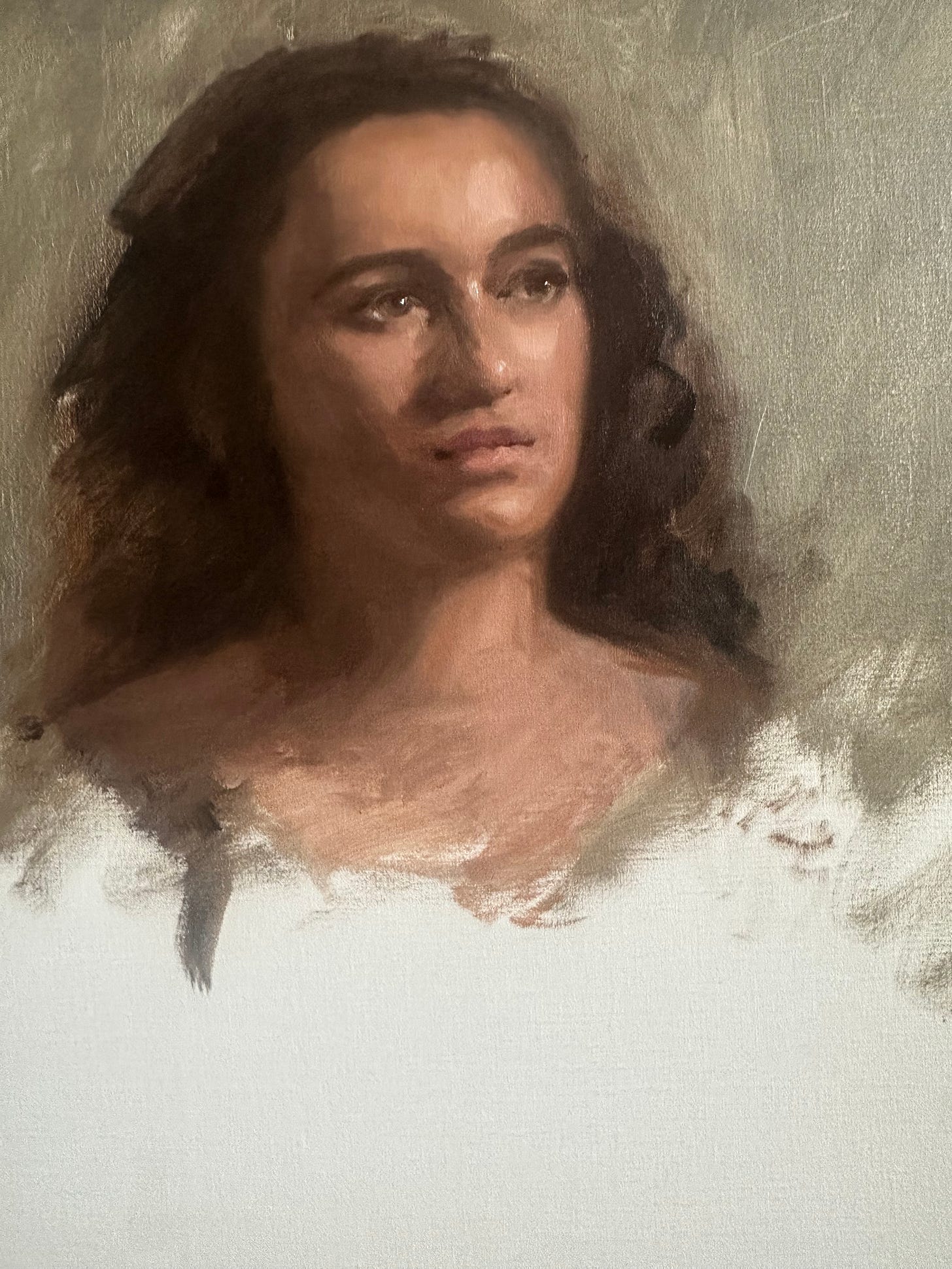

At the end of the week of painting, I stepped down from the plinth and looked at myself. I was baffled by the person staring back at me. I looked for clues about myself in each one: was that really how my mouth fell, how my cheeks rounded? I was fascinated by these things. But I didn’t feel any closer to myself, any more in order, any closer to some kind of truth about who I was. Being painted had not finalised anything about my constitution.

Over the week, I had taken photos of the portraits at the end of each day to see the process of the paintings. There are two progress pictures which I like the best. The first was at the end of the first day; I have no pupils or defining features, no colouring except a wash of black at the roots of my hair. Despite this, I can tell it is me, and I feel there is something recognisable in that empty outline. Perhaps the parting of my lips, the distance between the side of my nose and the edge of my cheek. Something else entirely, maybe. In the second process photograph, I have been painted very loosely, it is definitely me, but with soft, blurred edges. I look serene and calm, but in movement, too.